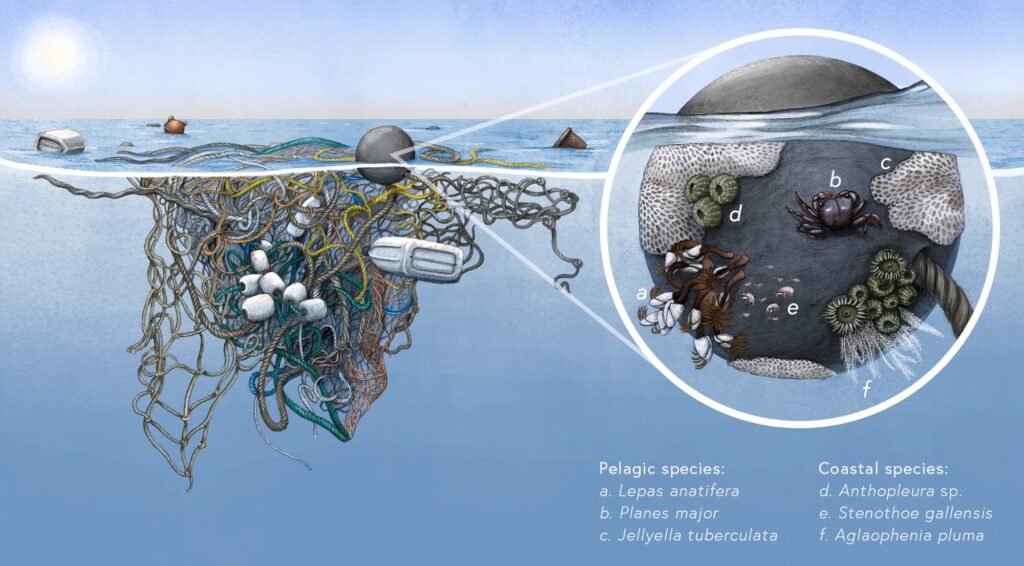

Life advances on the plastic island with coastal species that, for the first time, appear in the open sea; new colonies may expand from the North Pacific

The Island of Garbage or Pacific Plastic, or as it is popularly known, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, is an area of more than 1.6 million square kilometers, three times the size of France. It contains 100 million tons of plastic debris at the center of the North Pacific gyre, floating between California and Hawaii.

The Pacific Garbage Island emerged from the pollution of rivers, beaches and the ocean. Once the garbage reached the ocean, currents carried it toward a point called an ocean gyre, where the water stagnates like a drain.

Garbage works as an artificial reef that attracts food

It is the largest of the five garbage-filled gyres in the world: North Atlantic, South Atlantic, North Pacific, South Pacific and Indian Ocean. Spins are formed when debris leaves the sea by surface currents and is trapped in large masses by rotating currents.

ONE recent study Conducted by researchers at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), the University of Hawaii and the Ocean Voyages Institute, it found that many coastal species, including anemones, hydroids and shrimp-like amphipods, live in the mass of plastic debris.

They called these communities neopelagic, “neo” which comes from the Greek and means new, and “pelagic” also from the Greek pelagos which is the open sea.

Neopelagic community with plastic debris floating in the surface waters of the Pacific Ocean

Waste attract food

SERC Senior Scientist, Greg Ruiz, said the open ocean was not habitable for coastal organisms until now. Neopelagic communities are finding food thanks to the calm waters, whose residues act as a reef that attracts food.

The Ocean Voyages Institute team collected 103 tons of plastic and other debris from the North Pacific subtropical gyre that were analyzed by SERC scientists.

The main author of the study, Linsey Haram, explained that problems with plastic are creating opportunities for the biogeography of coastal species to expand far beyond what we thought possible.

The research team is not sure whether these colonies exist outside the North Pacific subtropical gyre. However, as global plastic waste production continues to increase, the team believes these neopelagic communities will likely continue to grow.

REFERENCE

Emergence of a neopelagic community through the establishment of offshore coastal species