O human genome sequencing over the past two decades has led to a deeper understanding of our evolutionary past. In this way, genomic data were generated from hundreds of thousands of individuals, including thousands of prehistoric people..

A team of scientists has applied a new non-parametric method that combines registration data into a genomic tree ancient and modern humanswhich allowed them to deduce a complete human genealogy.

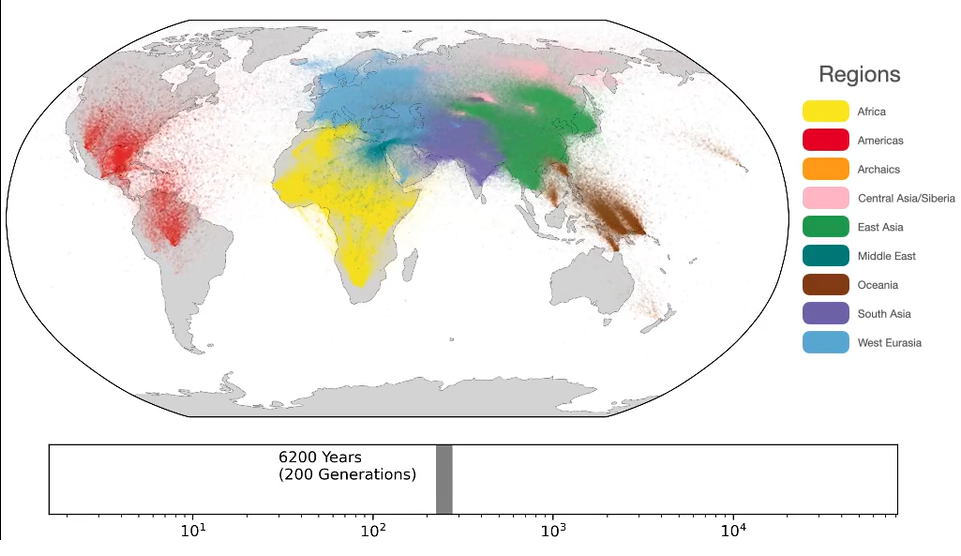

By treating all our ancestors as a single network, we can estimate general characteristics of common ancestors in the human family tree, such as their age and potentially even their location.

“A non-parametric method means that we had to make very few assumptions about the nature of human migrations. For example, we need not conjecture whether there was one, or only a few, migrations out of Africa, or that they took place in a certain way at a certain time. Our goal is to let the data speak for itself”, he tells SINC Yan Wongfrom the Li Ka Shing Center for Health Information and Discovery at the University of Oxford (UK) and co-author of the study published in the journal Science.

With this technique, the ancestor of two individuals is geographically assigned to the midpoint between the geographic location of their two descendants and their ancestors in the past are determined. “While we know this method is imperfect, it seems to recapitulate well many of the known human movements. Perhaps the surprise is, in fact, that it works reasonably well”, he tells SINC Aida Andrésfrom the Institute of Genetics at University College London and author of a article in the same magazineas a comment to this work.

To date, thousands of human genomes have been collected, containing segments from different and multiple ancestors of different ages. Consequently, building a comprehensive picture of genealogy and genomic variation throughout human history poses a technical challenge.

Now, Wong and his team have managed to build a huge family tree For all humanity. “By treating all our ancestors as one Internetwe can estimate general characteristics of the common ancestors in the human family tree, such as your age and even potentially your location. Our method can potentially scale to millions of genomes,” says Wong.

A unified genealogy of modern and ancient genomes. /Wilder Wohns

The story that spawned all our genetic variation

As individual genomic regions are inherited from only one parent, the ancestry of each point in the genome can be thought of as a tree. The set of trees, known as ‘tree sequence‘ or ‘ancestral recombination graph’, links genetic regions over time to the ancestors where the genetic variation first appeared.

In total, eight different databases were used, including a total of 3,609 individual genomic sequences from 215 populations. Ancient genomes included samples found all over the world, ranging in age from 1,000 to over 100,000 years old. The algorithms predicted where common ancestors needed to be present in evolutionary trees to explain patterns of genetic variation. The resulting network contained nearly 27 million ancestors.

Our pedigree shows, for the first time, that the signal for dispersal out of Africa is clearly present throughout the genome.

Anthony Wilder Wohnswho carried out the research at the University of Oxford and is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard (USA), points out to SINC: “Although this genealogy includes an enormous amount of detail, note middle age and location of ancestors provides a great overview of the general features of human history. Sometimes we can even display all this data to reveal important patterns.”

After adding location data from these sample genomes, the authors used the network to estimate where common ancestors lived. The results successfully recapitulated key events in human evolutionary history, including the migration out of africa.

“It has long been known that there was a dispersion of this continent, perhaps around 100,000 years ago. The signals for this event are found in parts of the genome, such as the mitochondrial, the Y chromosome, and several other genes. However, our genealogy shows for the first time that the signal for this event is clearly present throughout the genome,” says Wong.

The researchers observed signs of ancestral lineages very deep in Africathe event outside Africa and the archaic introgression or incorporation of genes in Oceania.

The mutations that give us the clues

This method also takes into account the missing and wrong dataand uses fragmented ancient genomes to help pinpoint the timing of alleles.

“These are genetic variants. They appear by mutation at some point, and if they are established from that point on, this genomic position will be variable in the population. Some chromosomes will have one allele, others the other. We can infer the age of these alleles using modern genomes, but it is a difficult problem and we do it with low resolution”, reveals Andrés.

The genomic datasets we used were constructed from many different sources and using different methods. Inevitably, certain types of errors occur. Our approach helps you identify them

What they did in this study was use low-quality old genomes to help determine their age. For each allele, they wondered when they first saw it. If, for example, you look at a genome from 5,000 years ago, you’ll know for sure that this mutation is older than that.

“This helps improve models that allow us to infer human demographic history. But beyond that, if this allele has important effects — for example, if it allows us to digest lactose or if it increases the risk of a disease — improving allele age inference helps us understand the history of that allele. phenotype or this disease,” continues the University College researcher.

Gil McVeananother of the Oxford University co-authors, emphasizes to SINC: “The sets of genomic data that we use were built from many different sources and using different methods. Inevitably, certain types of errors occur. Our approach helps you identify them. We estimate the rate to be small, less than 0.5% of the variant loci in the genome, but its removal creates a more accurate and complete picture of human genomic variation.”

Although the study focuses on humans, the method is valid for most living beings.

Study limitations

Wilder Wohns, in turn, explains that one of the main limitations of this work is that they use a very simple method to estimate the location of our ancestors.

“Much more could be done in this field. Furthermore, our estimates of the location of ancestors are ultimately limited by genomic sequences. For example, the accuracy of our reconstruction of migrations of indigenous peoples to the Americas is hampered by the relative scarcity of samples from northeastern Siberia and northwestern North America.”

Furthermore, if there were great historical migrations that left no local descendants, the accuracy of such ancestor location estimates would be diminished.

One of the biggest limitations of any study using the large existing genome databases – including this one – is that we do not have an adequate representation of all human populations.

Finally, the method takes into account the errors of the genetic datasets used, but it does not do it perfectly. This can also affect the age and location estimates of our ancestors.

“From my point of view, one of the biggest limitations of any study that uses the large existing genome databases – including this one – is that we don’t have a adequate representation of all populations human. Databases are biased towards well-studied populations. For example, Europeans. But this happens, not only in this research, but in most of the current genomic works, and it will only be solved by sequencing more genomes from more world populations”, concludes Andrés.

Reference:

Anthony WilderWohns et al. “A unified genealogy of modern and ancient genomes”. Science